What Are We Here For? Q&A with Sam Daley-Harris

by Anna Awimbo | September 19, 2013

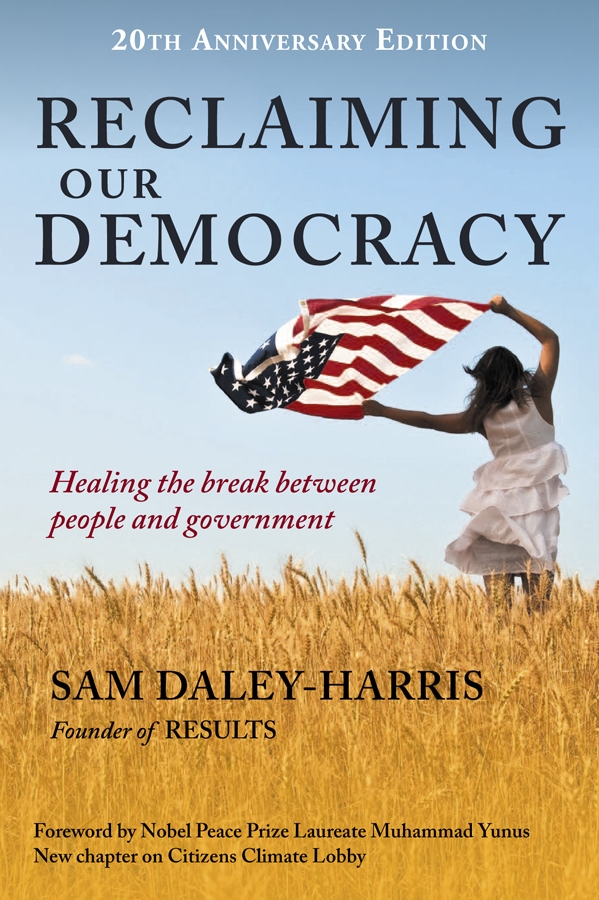

New Dream spoke with Sam Daley-Harris about the 20th anniversary edition of his book, Reclaiming Our Democracy.

Sam is CEO of the Center for Citizen Empowerment and Transformation, a nonprofit organization that works with the leaders of networks and institutions to create support structures that empower their members—ordinary citizens—to create champions in Congress and the media for their cause.

The first edition of Reclaiming Our Democracy came out 20 years ago. What prompted you to write the book?

What prompted me to write the book is what prompted me to form the organization RESULTS. I had none of the background that you would normally think of when you think about an activist. I have degrees in music and was playing in the Miami Philharmonic Orchestra and teaching music.

But when I look back, there are two pivotal moments of my life that come to mind:

At my high school graduation, I learned that a fraternity brother had died the day before in a tractor trailer accident. I was 17, and, like most young people that age, I thought I had forever. But with this death, the funeral, and the mourning period, I began to think that maybe I had just 17 more minutes. I began wondering, “Why am I here?” “What am I here to do?” “What’s my purpose?”

Four years later, on the day of my college graduation, Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated, and again I was consumed with thoughts of, “What is this life?” “What is this death?” “What am I here to do?” There were no answers yet, but the questions were getting clearer. It reminds me of the Mark Twain quote, “The two most important days of your life are the day you are born and the day you find out why.”

Nine years later, I attended a presentation on The Hunger Project. I rarely thought about world hunger before this. I was mostly oblivious to it, but if you lifted up the oblivion, underneath that was mostly hopelessness. If somebody had asked me about world hunger, I would have said there were no solutions because if there were, somebody would have done something by then. At the presentation, it became obvious to me that there was no mystery to growing food, no mystery to clean water, no mystery to basic health. I realized that I wasn’t hopeless about the lack of solutions, I was hopeless about human nature. I felt that people would just never get around to doing what needed to be done.

There was one human nature, though, that I had control over: my own, and my questions, “Why am I here?” “What am I here to do?” So I started to get involved.

In your book, you talk a lot about groundbreaking work by “ordinary citizens.” Can you give us an example of what you mean?

The whole reason for the book is to bring people to the realization that we don’t have to be cynical, we don’t have to feel hopeless, and we don’t have to be discouraged and feel turned off by politics and government, or be cynical about our ability to make a difference.

Instead, we can be turned on, lit up, and in action—and we can really turn things around.

Here’s an example: In 2007, I got a call from Marshall Saunders, who was a volunteer in RESULTS at the time, and he said, “I saw Al Gore’s documentary, An Inconvenient Truth, three times in 10 days. Then, I went to Nashville as one of a thousand people who went to be trained to lead the [documentary] slideshow. I went home to San Diego and I led it 43 times. Early on, I realized I was giving people 98% of the problem and 2% of what they could do about it. I also realized that they couldn’t buy enough Priuses or change enough light bulbs to make up for what the government was or was not doing.”

He later said, “I was reading the paper one day, and one of the articles said that Congress had just approved $18 billion in subsidies to the fossil fuel industry. I realized that I had convinced 18 people to change their light bulbs that day when the government had appropriated $18 billion in subsidies! And I thought, 'This is never going to work.'” He continued, “I realized that this movement needed a grassroots political voice.”

Marshall talked to a couple of environmental groups and asked them to consider taking a small portion of their members and training them to be deep advocates on climate issues. They all said no. So, he came to me and asked me to coach him in starting the Citizens Climate Lobby. In October 2007, he held his first meeting. He had no groups and no volunteers. At that first meeting, they had 29 people in the room. At the end of the meeting, they all raised their hands and said they wanted to be involved. They started three chapters. Three chapters of Citizens Climate Lobby, all in one county in the United States.

Today, Citizens Climate Lobby has 121 chapters in the United States and Canada. In the first eight months of 2013, its volunteers had 745 letters to the editor published, 141 op-ed pieces published, and 602 meetings with members of Congress or their staff, including face-to-face meetings with House Majority leader Eric Cantor—generated by the grassroots groups, not the CEO. They also had a face-to-face meeting with House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan—generated by the grassroots groups. This is some really powerful work that’s going on.

What challenges still remain?

From my point of view, the big challenge is in finding or providing a really rich curriculum for volunteers. Twenty years ago, almost no groups were doing monthly conference calls and meetings. Today, a number of groups hold conference calls and webinars. But if you sit in on them, they can often be kind of wonk fests, kind of boring, not rich, not profound, not deep.

The deepest challenge is for advocacy staff to provide—and for volunteers to find—a deep structure of support that really gives the necessary information and empowerment that allows for transformation from the mindset of “I can’t make a difference” to “I can make a difference.” From “I can’t fight City Hall” to “I am City Hall.” That’s the challenge. Building an ongoing structure of support and focus so people can become lit up and moved to action. There are lots of other challenges, but you’ve got to overcome this challenge first so that people don’t drop out, get discouraged, or give up because they have no support.

Can you recommend a favorite chapter from your book for New Dreamers to focus on?

I love them all. It’s almost like asking, “Which of your children is your favorite?” I think New Dream members will find the two new chapters most relevant—chapter 29, focusing on the Citizens Climate Lobby, and chapter 30, focusing on the Center for Citizen Empowerment and Transformation. These chapters are great because they’re filled with stories of people climbing over their hopelessness and discouragement, getting into action, and experiencing a transformation—a transformation in their relationship with their government, and a change in who they think they are in the world.

You know, everyone wants to matter, and there’s this great quote from Apollo astronaut Rusty Schweickart that goes: “We aren’t passengers on Spaceship Earth, we’re the crew. We aren’t residents on this planet, we’re citizens. The difference in both cases is responsibility.” That’s what Reclaiming Our Democracy is all about.

Where can folks find the book?

The book is available through the website, www.reclaimingourdemocracy.org.