The “Gendering” of Our Kids’ Toys, and What We Can Do About It

by Elizabeth Sweet | October 7, 2011

As a child growing up in the 70s and 80s, I don’t recall feeling that my toy choices were particularly limited because of my gender. I played with both dolls and trucks and had the most fun just making mud pies in the backyard. Maybe this was the result of being raised by parents who didn’t impose traditional gender ideas on me, or maybe it was just emblematic of the times.

But when my daughter Isabella was born in 2002, I began to notice how extremely gendered children’s products seem to have become in the new millennium. Trying to find girls’ clothing that was not pink (which I quickly learned isn’t a very functional color for a toddler who loves to grub around in the dirt) was enough of a challenge. But it was in the world of toys that I noticed what seemed to be a drastic change from my own childhood.

With the exception of preschool toys that were sometimes offered in gender-neutral packaging, kids’ toys were largely segregated into different aisles (or online pages) according to gender. And within those aisles, the markings of gender were clear. The “girls’” section resembled the aftermath of an explosion of Pepto-Bismol. In the “boys’” section, there seemed to be a profusion of aggressive, hyper-muscled, weapon-wielding action figures. And in both realms, the majority of toys seemed to be explicitly tied to movies and television.

I sought out non-gendered toys for my daughter and found them more readily available in higher-end, independent toy stores—but they also came with a hefty price tag. And even these alternative toy markets seem to be becoming more and more gendered. Just the other day, while shopping with my daughter at the local independent toy store for a birthday gift, I couldn’t help but notice that Melissa & Doug brand crayon sets are offered in two versions—a pink princess model and a blue fire-truck version.

Of course, I’m not alone in noticing how today’s toys seem increasingly gendered. In their books Packaging Girlhood and Packaging Boyhood, authors Sharon Lamb and Lyn Mikel Brown detail the extensive and problematic stereotypical messages about gender that are embedded in contemporary children’s products and advertising. Peggy Orenstein’s book Cinderella Ate My Daughter explores the pink-laden, hyper-sexualized “girlie-girl” culture that is omnipresent in the U.S. today, and the consequences of this culture for both children and parents. And scholars of children’s marketing such as Juliet Schor and Susan Linn have offered extensive evidence of how such trends are connected to commericalism’s omnipresence in the lives of children in the attempt to create cradle-to-grave brand awareness and loyalty.

Ever-more targeted marketing that segments and isolates children into specific categories (“tween girls,” for example) may explain why toys are becoming more ostensibly gendered. But a larger question remains: In light of the significant advances toward gender equality that we see in the occupational realm, in the realm of home and family, and in education, why do children’s toys seem to be moving in the opposite direction? Why are they embodying seemingly regressive stereotypes—i.e., that girls are sweet, domestic, and pretty, and boys are strong, aggressive, and mechanically inclined? And why has gender become such a focal distinction among marketers and toy producers?

The Historical Context: Trends in the 20th Century

It was this question that led me to my dissertation research project. I wanted to put what I was seeing in a historical context, and to understand whether it was indeed true that toys today are more gendered than they were, say, in the 70s and 80s. Has there in fact been a change in the extent to which children’s toys are made and marketed according to gender? And how do the changes in children’s toys relate to larger social shifts in gender relations? Do toys merely reflect the ideas about gender that are predominant in the larger culture at any given time, or are they a reaction to these ideas, either promoting more or less egalitarianism than is the case at any given time?

To address these questions, I’ve spent the past year analyzing the content of toys and toy ads in a sample of Sears catalogs from the 20th century—a primary site of consumption for Americans during this time. I’m examining both the images and the text to determine how much the toys and ads are overtly and subtly marketed toward a particular gender, and how this is evident. I'm attempting to ascertain who a particular toy was designed for, and what kinds of qualities and attributes are being ascribed to both the toy and the child. I’m still in the process of data analysis, but already I’ve observed some interesting trends:

The sheer number of toys produced for and marketed to children has increased exponentially over the 20th century. In the 1905 Sears catalog, there were only 139 toys offered, including card and board games for the whole family. But by 1945, the number of toys had nearly doubled, and by 1995 there were over 1,400 toys on display in the Sears holiday Wishbook. This makes sense in light of the changing understandings of childhood and the shifting patterns of consumption over the course of the 20th century. At the turn of the century, children were productive contributors to the family economy and thus childhood was viewed far less than it is today as a unique and protected status. In addition, the explosion of the toy market in the second half of the 20th century surely reflects the simultaneous rise of the consumer economy where children are now seen as vital consumers.

The extent to which children’s toys are overtly gendered (i.e., explicitly marketed to either a boy or a girl in the ad copy) appears to have fluctuated over time, but it is clearly a dominant trend today. For example:

- In the 1905 catalog, no toys were expressly marketed to either gender, and only a handful (roughly 15 percent) bore more subtle gender messages. Even the dolls, which in subsequent decade were much more clearly marked as “girls’” toys, were advertised in a fairly gender-ambiguous manner. And some dolls were clearly designed for boys as well as girls.

- By 1915, dolls tended to be much more feminine in form (with hair bows, for example) and doll accessories were overtly marketed toward girls. We also see the emergence of homemaking toys, such as toy stoves and irons, which are expressly made for girls, and toys such as guns, model kits, and tool sets, which were expressly marketed for boys. But the majority of toys in the early part of the century—blocks, stuffed animals, farm sets, balls, pull toys, etc.—seemed to lack the markings of gender.

- By mid-century, nearly all dolls were overtly marketed toward girls, as were home-making toys. Fewer toys seemed to be expressly marketed toward boys. While some bore the subtle markings of gender (i.e., being modeled by a boy), only a handful of guns or trucks were overtly directed toward boys. Yet clear gender distinctions had emerged in terms of occupational roles, as is clear in a 1945 ad for “Doctor and Nurse” kits.

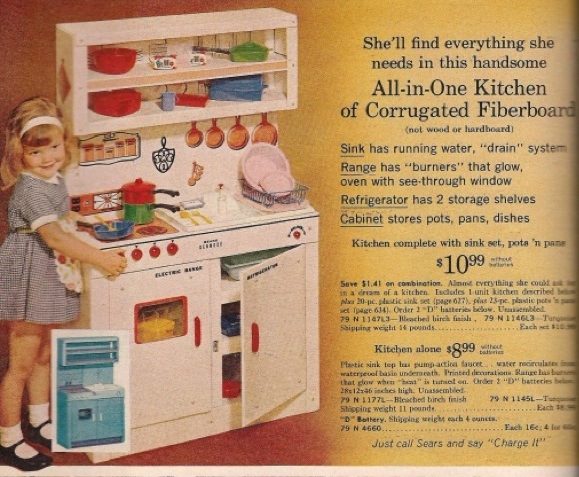

- By 1965, the gender roles that prescribe the realm of home and family to girls and the realm of science, building, and aggression to boys were even more evident. In one catalog, we see an image with the caption: “Sears knows what little girls like...” and on the opposing page, “Dolls daintily dressed in parfait colors.” The kitchen seems to be strictly for girls (as depicted in the first ad shown above), and girls’ dress-up clothing is framed around the ideas of dating and romance. In contrast, the realm of science is portrayed as the domain of boys, and there are a profusion of toys like G.I. Joe that embody aggression marketed to boys. Yet there are still some toys, primarily toddler toys and those designed to be educational, that remain gender neutral

- Interestingly, by 1975 we begin to see some broadening in the gender roles that are prescribed for boys and girls and in the extent to which toys are overtly gendered. Overall, there seem to be fewer toys than in previous decades that are explicitly marketed toward one gender or another, although there are still subtle forms of gendering (such as the use of color or the wording of ad copy). We also see, for the first time, images of boys playing with kitchen playsets and girls playing with construction sets. And the image that goes with the “doctor and nurse kits” is one of two girls.

- These trends become even more pronounced by 1985, where we see boys not only in the kitchen but also modeling home-making toys such as vacuums. And we see, for the first time, images of boys playing with dolls. For girls, we see the introduction of action figures such as “She-Ra” that embody both femininity and adventure. And boys and girls seem to be more likely to share space on catalog pages and to wear clothing that is less gender typed than in previous decades.

- Notably, by 1985, the majority of toys offered in the Sears Wishbook are clearly branded where they were less likely to be previously. And many are clearly tied in with children’s television programs and movies. In 1984, deregulation removed the legal barriers that prevented the use of children’s programming to sell products. The profusion of branded toys that directly relate to programming in 1985 is likely a direct result of such deregulation.

By the end of the 20th century, there were signs that the move toward more gender-neutral toys and toys that embody increasingly egalitarian gender roles was waning. In the 1995 holiday Wishbook, although we still see some images of boys in the kitchen and girls doing science, the use of pink to color-code “girls’” toys and playsets seems more prevalent than ever. Some toys, such as beds and building sets, are offered in separate versions according to gender. Although few toys are explicitly stated to be for a particular gender, many show the subtle markings of gender through use of color, specific models, and language in the ad copy. It seems reasonable to assume that few boys will select the pink Fairytale Princess bed or the Fairytale Palace Mega Bloks. And in fact, the gendered Mega Bloks sets are an interesting contrast to the relatively gender neutral Lego sets found in the previous decade.

Toys and Gender: The Larger Picture

In the 1990s, toys aimed at girls often emphasized beauty, nurturing, domesticity, and romance while boy’s toys seemed to emphasize aggression, action, and excitement. Although these types of gender messages are evident to varying extents throughout the 20th century, they seem heightened in the mid-90s compared to the previous two decades. This is the same period that women were showing an increasing presence in the labor force, in the political realm, and in higher education.

As gender relations continue to move toward a more egalitarian end, why then do toys seem to be moving in the opposite direction?

One possible explanation for this trend is that as women have gained social and political power, toys have come to embody an ideological backlash to this progress. As the roles of men and women become more similar in the larger society, there is a greater need to distinguish between masculinity and femininity within the culture, and to emphasize that the traditional aspects of gender roles have not been abandoned.

But toys also serve a critical role in teaching children about gender and what it means to be masculine and feminine, so the heightening of gender in the realm of toys seems especially problematic. How do children come to understand that men can be nurturing and can cook and care for the home, and that women can be assertive, adventurous, and competent, when the ideas they see encoded in their toys are so contradictory?

The effect of these messages on children may be more profound than we might think. From my own experience raising a daughter who has always eschewed anything pink and princessy, I know it can be difficult being a child who doesn’t conform to these increasingly rigid gender norms. For girls, there is still some latitude to stray across gender boundaries—girls can, for example, wear boys’ clothing or play with boys’ toys without being socially ostracized. But for boys, the stakes are higher. Consider the massive controversy that arose when J. Crew ran an advertisement that showed a mother painting her son’s toenails pink.

This past holiday season, I found myself in a Toys ‘R’ Us store and couldn’t help but notice, in the virulent pink “girls’” section, the signs above the toys that said “cook and clean” and “kids’ cooking.” I couldn’t believe that, in the year 2010, this is where we are in terms of gender and toys. While the language on the signs may suggest gender neutrality, the use of color clearly suggests that these tasks are the domain of girls.

This past holiday season, I found myself in a Toys ‘R’ Us store and couldn’t help but notice, in the virulent pink “girls’” section, the signs above the toys that said “cook and clean” and “kids’ cooking.” I couldn’t believe that, in the year 2010, this is where we are in terms of gender and toys. While the language on the signs may suggest gender neutrality, the use of color clearly suggests that these tasks are the domain of girls.

I am troubled by what I see as a move toward more repressive ideas about gender in the land of children’s toys, and I’m also concerned about the constant push to consume and spend for children from birth onward. The manufacturers who make the bulk of children’s products, and the marketers who sell them, generally do not have children’s best interests at the forefront. Rather, the desire to profit is paramount, whatever the social cost.

As parents, we need to become more aware of the messages being sent to our children via marketing and the products they are surrounded by. And we need to educate our children about those messages. I talk constantly to my own daughter about what I see, and as a result she has begun to decode those messages herself. That doesn’t mean she still isn’t swayed by them from time to time, but at least her eyes are open.

But most importantly, as citizens, we need to demand that corporations be held accountable to make and market products in a responsible manner. Left to its own devices, the toy industry seems loathe to address the negative effects of contemporary toys and toy marketing for children. Thus, pressure from citizens and parents will be necessary if we hope to see a future where children’s products aren’t at such odds with important values like gender equality.

To learn more about how you can combat the harmful effects of commercial culture on children, visit:

- New Dream's Kids & Commercialism campaign

- The Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood Website

- Consuming Kids: The Commercialization of Childhood Film on YouTube

- Sociological Images Blog, which offers many examples of gendered products and advertising

Elizabeth Sweet is a doctoral candidate at the University of California, Davis. Her research interests include sex and gender and the sociology of the family. She is the mother of a 9-year-old daughter, Isabella.