Community Building Through Peacemaking Circles — and Dinner

by Jessica Laus | June 26, 2018

I grew up in a multi-family home a few blocks from the Detroit River, in a section of the city that had been largely abandoned, save for the occasional attempts at redevelopment. In that neighborhood, where old houses were separated by empty lots long reclaimed by nature, I witnessed the community work to overcome insurmountable odds, and even then I witnessed a stubborn sense of resilience and hope, as exemplified by the small acts of kindness that neighbors and business owners extended to one another.

In first grade I began attending Friends School, a small Quaker school within walking distance of downtown that was largely insulated from many of the issues that plagued the city at large. Founded in 1965 by Wade and Dores McCree after their daughter was denied admission to a private school in Detroit based on the color of her skin, they wished to establish a school that would be welcoming to all. The Quaker values of peace, community, and stewardship, among others, created just that, and without realizing it at the time, the school’s dedication to circle dialogues, moments of silence, and commitment to equality were my first introduction to restorative principles and peacemaking circles.

Peacemaking circles, according to Kay Pranis, a national leader in restorative justice, draw on Native American traditions and are combined with contemporary concepts of democracy and inclusiveness. They are first and foremost a storytelling process, and they bring people together as equals in order to have honest, and at times difficult, exchanges in an atmosphere of concern and respect for all. Circles are intentional structures that invoke equality, and may be used for celebration, to talk, to create understanding/resolve conflict, and to build community, among other uses.

"Peacemaking circles. . . draw on Native American traditions and are combined with contemporary concepts of democracy and inclusiveness."

When I moved to Newark, New Jersey, a city with many of the same characteristics as Detroit, I sought to find the sense of community that I felt in my hometown. I applied to volunteer at the Newark LGBTQ Community Center, where I was warmly welcomed as an ally, and at around the same time I attended an event co-organized by Restorative Justice Initiative, which I also offered to support. In February 2017, RJI sponsored my enrollment in a peacemaking circles training with Kay Pranis, and I soon began co-hosting an event at the Center called “Community Dinner.”

Community Dinner has become a space for the LGBTQ community, friends, and allies to connect with one another on a regular basis, to break bread, and to participate in a group discussion, although it’s not obligatory. Guests are encouraged to bring a dish to share or a small donation, although no one is turned away for lack of funds, and on more than once occasion we have welcomed our homeless community into the space to join us.

How It Works

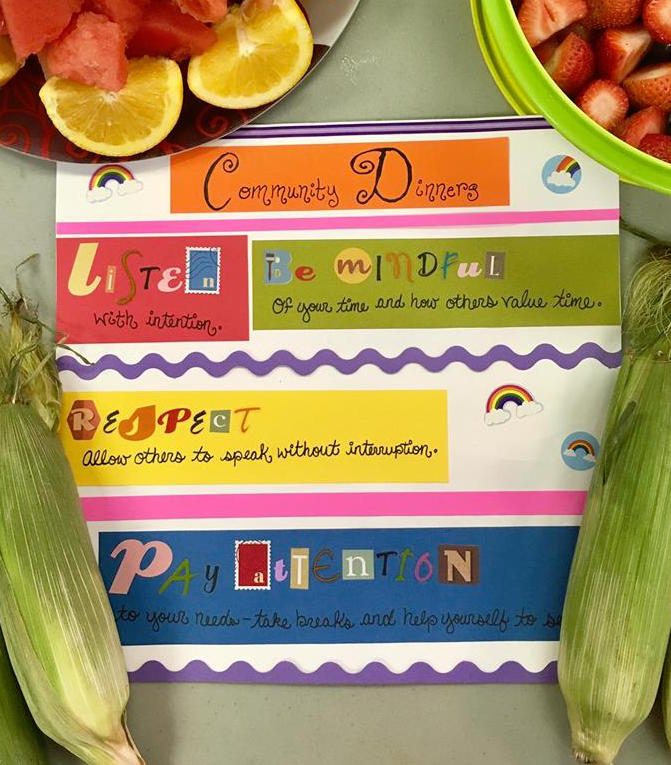

We begin with a moment of silence to collect our thoughts, after which we go around the table to introduce ourselves and quickly discuss what brought us to the table that day. I then review pre-established guidelines for the discussion, which include allowing everyone to speak in turn without interruption, and paying attention to one’s physical, emotional, and mental needs.

Guests are welcome and encouraged to add to or modify the guidelines as they see fit. Once the guidelines are agreed to, I pose a prepared question to the group, which everyone is invited to answer and reflect on, unless they choose to pass their turn. Topics may range from pets to politics, and can become very personal and open as the discussion progresses.

The meal and discussion usually last for approximately two hours and generally conclude naturally. They are democratic in nature and allow a space for everyone to share and discuss their experiences and ideas, or to simply listen. We have had smaller, more intimate dinners with 4-5 guests, and at our largest dinner we were joined by upward of 30 guests.

We welcome all, provided they are respectful of the space, and we are humbled when individuals from around the region travel to the Center to join us. I have witnessed trust, empathy, and friendships flourish in these safe spaces, and at times these dinners have become avenues for local leaders to listen to the concerns of the LGBTQ community and its allies.

To begin a similar community-building event utilizing restorative principles, I have found it useful to begin with an organization that has already been established as a platform (this could mean a community center, a library, or a non-profit organization, for example), and being very open and transparent with what you hope to accomplish and what guests should expect. We also work hard to ensure that everyone can join us at the table regardless of dietary restrictions, and that everyone who comes in the door is warmly welcomed on an individual basis.

It’s also critical for the circle facilitator to come to the space relaxed, ready to listen, and prepared with potential questions/ideas for conversation. I enjoy keeping circles because it’s an opportunity to listen to others’ stories, and I find that my focused attention on each storyteller sets the tone for the dialogue as a whole. When the guidelines are established and agreed to from the start, guests will naturally adhere to them, and on the occasion that someone has much to say, I remind myself of the catharsis of sharing, and how irregularly some of us have the opportunity to truly be heard.

"I enjoy keeping circles because it’s an opportunity to listen to others’ stories, and I find that my focused attention on each storyteller sets the tone for the dialogue as a whole."

I am grateful for the opportunity to bring members of the community together to work on building and sustaining a sense of belonging to one another and to the city that we share.

Further Reading

The Little Book of Circle Processes: A New/Old Approach to Peacemaking by Kay Pranis

The Little Book of Restorative Justice by Howard Zehr

Jessica Laus is a development professional who has volunteered for non-profits in the fields of historical preservation and education, adult literacy, adolescent mentoring, LGBTQ rights, animal welfare, and restorative justice for over 10 years. She is also the founder of ID US, which raises awareness and provides information about how to secure government-issued photo IDs in the United States and its territories.