Film Review: “Sorry to Bother You”

by Alexis Arambul and Sarah Allison | September 13, 2018

In this review, New Dream Youth Fellows Alexis Arambul and Sarah Allison have a conversation about Boots Riley’s cringe-inducing satire of racism and capitalism in America.

About the Film

Boots Riley’s latest film project, “Sorry to Bother You,” hit theaters in summer 2018. The movie is set in Oakland, California, and follows Cassius Green, a seemingly normal guy just trying to get by. Cassius takes a job at a telemarketing company where he’s told to “stick to the script.” As he adjusts to his new role, he makes friends with a few of his coworkers, including Langston (played by Danny Glover), who advises him that a key to making sales is using his “white voice.”

We learn that the “white voice,” in telemarketing, is selling a pitch like you’re worry-free and have your life put together. The voice is several octaves higher and is about emanating a carefree energy—absolutely no desperation allowed. Cassius masters this skill swiftly and soon moves up the corporate ladder, all while trying to balance his relationships with his partner and his new work friends, who have not been as successful as him. As Cassius becomes more successful, his coworkers plot protests against their company. This creates the main conflict in the film: will Cassius choose his own prosperity, or the collective care of his fellow workers?

A Conversation

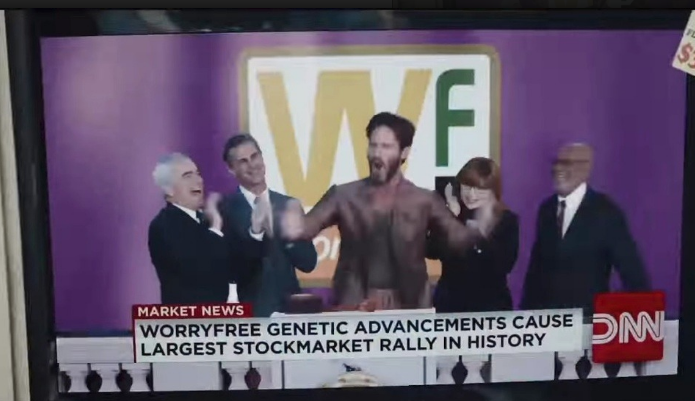

AA: One of the major clients of Cassius’ telemarketing firm is “WorryFree,” a company that promotes waste reduction and downsizing. How do you see this as contributing to the film’s narrative?

SA: WorryFree promotes downsizing and limiting waste, but all while subjecting the people who work in its factories to harsh labor conditions and cramped, inhumane living conditions—under the guise of “stability.” It’s a front for taking advantage of the workers while being able to make a profit off of them. There’s even a scene in the film that shows a liquor store with a WorryFree ad tagged over that reads, “slavery at work.”

WorryFree’s role illustrates an important point about how movements and ideas can be co-opted, and how it’s important to look below the surface. In theory, downsizing and living minimally have taken hold in our society because of the positive impact they might have on our carbon footprints and in addressing our alienation from each other. However, in this case, the downsizing is only in the name of cutting costs on taking care of workers.

"In theory, downsizing and living minimally have taken hold in our society because of the positive impact they might have. . . . However, in this case, the downsizing is only in the name of cutting costs on taking care of workers."

This reminds me of the “who pays” question that the creators of the short animation The Story of Stuff address: when consumers are offered cheap prices, it’s only because they’re not assuming the full costs of creating a product, and the gap is absorbed by various people along the chain of production.

AA: How does the film demonstrate the power of the collective—of community organizing—when confronting powerful corporations?

SA: At one point in the film, an unnamed female protester throws a soda can at Cassius’ head as he heads into work with the other “Power Callers.” As a Power Caller, he gets to take the golden elevator to the top of the building, and one of the acts of protest among his fellow workers is trying to use force to prevent him and others from getting inside. The community uses Cassius’ run-in with the protester as a symbol for their cause of unionizing and agitating against unfair wages and labor conditions. This makes for a good symbol because the action goes viral and is a physical “win” against the company.

It’s important to note that the girl who throws the soda can ends up “selling out” by becoming the face of the soda company, which seems to illustrate the ways that movements/protests can take a negative turn. This reminds me of an incident that happened in real life with the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. A photo went viral of a BLM protester facing a line of heavily armed policemen, with her hand up in a peaceful attempt to keep them from using force against the crowd. In an insensitive twist on this, celebrity model Kendall Jenner recreated the action in a Pepsi commercial, going up to a line of policemen and handing one of them a Pepsi. The commercial sparked outrage by making a mockery of the movement.

SA: What does the film’s use of satire—through its display of “code switching” (the voice that Cassius assumes when he’s on the phone or at work)—say about corporate culture in the U.S.? Is satire a useful tool for social change?

AA: The code switching in the film signifies that, in order to be successful in corporate America as a person of color, you need to not only to work extra hard to be given the same opportunities, but also to compromise who you are. For example, in one scene Cassius goes to a work party where the CEO tells him to rap. Cassius says he doesn’t know how to, and then all the white people start chanting “RAP, RAP, RAP” (assuming that because he’s black, he knows how to rap). He ends up just saying the same thing over and over again using the “n” word while they chant it back at him.

Another memorable element of satire related to code switching occurs when Cassius “drops in” to the homes that he’s calling to give the audience a visual reference for when he uses his regular voice versus his “white voice.” Satire is also powerful in the company’s “stick to the script” rule, which symbolizes how corporate culture often forces you to go with the norm—how things have always been—and to never question when something is unjust.

I think satire can be used as a tool for social change in some cases, but not all. When satire becomes more offensive and less effective, and the message is hidden behind a veil of bitterness, it isn’t satire anymore—it’s just an attack method. But I think it’s done correctly in the film.

SA: What are your thoughts on Cassius’ girlfriend (Detroit) functioning as his consciousness—the voice of reason, per se?

AA: I’m a little conflicted on this one. On the one hand, I love the strong, independent, confident woman that Detroit’s character is: a “rebel” for a good cause and a good representation of the modern woman. But the other part of me feels like she’s meant to be a stereotypical version of a feminist in current culture. For me, Detroit is on the line of satirizing modern feminism while also reinforcing a stereotype of modern feminism.

I got major “Quentin Tarantino” vibes when watching her on screen. Tarantino is all about over-exaggeration in his films: playful use of color and loud/dramatic music. Detroit seems like she’d be a character in one of his movies, from her statement earrings, to the music that plays when she flips her signs at the sign shop (making it look like she takes her job seriously but not too seriously), to her dramatic art show in which she uses her own version of the “white voice.”

AA: As Cassius climbs the corporate ladder, he eventually meets the CEO of WorryFree, who shares that he’s designed a drug to turn his workers into horse/people hybrids—”equisapiens”—to make them stronger and more efficient. At the end of the film (spoiler alert!), Cassius himself turns into an equisapien. What do you think this means?

SA: For me, this transformation symbolizes the danger of living in a capitalistic society, and the insidious, viral nature of the ideologies that protect and uphold capitalism— white supremacy, heteropatriarchy, and the systems of oppression through which they manifest.

When Cassius turns into a horse, it’s like a “gotcha” moment, a wake-up call. Even though he ultimately walked away from the huge salary that the CEO offered him, chose to align with his coworkers and the union they were building, and turned his back on Worry Free, he did not emerge unscathed. He was still “infected’ with the evils of the institution to which he briefly pledged allegiance. This transformation compels viewers to notice the ways that we all are “infected,” and how we might heal. For me personally, it highlights the need for vigilance and continued attention to the ways that these systems show up in my own life, psyche, and behavior.

AA: Cassius Green compromises his values as he starts to move up the corporate ladder. What are some of the ways that minorities and low-income people compromise (or are expected to compromise) to “succeed” in America?

SA: This question makes me think of the ways that our society’s most violent institutions—departments of corrections, police departments, the military—all of which disproportionately surveil, kill, and dominate communities of color, also disproportionately recruit from communities of color. At Rikers Island in New York, for example, the great majority of corrections officers are of color (specifically Latinx and Black).

I think it’s easy to point a finger at these folks and say, why are you choosing to harm your people in this way? However, it’s also important to consider that these jobs offer a living wage, benefits, and pensions, and are secure. For folks who come from economically marginalized communities, they can be a path toward economic independence.

This question is connected to the earlier one about corporate culture. I think in modern corporate culture, there is a paradigm about “diversity and inclusion” that is really about how to teach people of color to “play nice” and blend in with the white majority—because of the power that white people have in this society. I imagine that code switching (especially when you’re being forced to do it) can feel like a very straining and taxing dynamic, and a huge sacrifice.

AA: What role does the media play in relation to large corporations. and what are some examples that you pick up in the movie?

SA: Most mainstream media acts as “smoke and mirrors” for large corporations in our country, by distracting us from the impacts that these corporations are having on workers and the planet. Something like five or six corporations own the vast majority of news outlets in the United States, which means that only a small sliver of stories are getting told. In the film, an example of this distraction mechanism is a popular show in which people get beat up, which brings to mind some actual popular reality TV shows or viral videos that are so ridiculous and/or cringeworthy that people get hooked.

"Something like five or six corporations own the vast majority of news outlets in the United States, which means that only a small sliver of stories are getting told."

Keep in mind that when all of the media’s attention is focused on shows or videos like this, it’s not being placed on things like the bills being debated in Congress, or what’s happening to the Amazon rainforest, or whatever other political/economic/social news is happening at the moment. The media also acts as rose-colored glasses, both in the film and in real life. Throughout the film, we see ads for the WorryFree live-and-work space, which is always painted as a positive development—but it comes at the expense of the masses. As viewers, we know that the company is exploiting its workers (forcing them to work long hours, eat disgusting food, and live in overcrowded conditions) to widen the corporation’s profit margins.

Much of the film is exaggeration, but it points to the unfettered power that corporate executives wield in terms of the narratives that the media uplifts, which do not need to be factual or accountable to viewers. To add insult to injury, many media outlets rely on advertising revenue from these very corporations, a reliance that further beholdens them to whatever euphemisms, cover-ups, or distractions that corporate public relations teams want to spit out.

Final Take on the Film

Ultimately, Sorry to Bother You proves to be a very successful satire. Many of the characters and symbols seem like extreme exaggerations, such as WorryFree and its executives. Yet the power dynamics that the film reveals are not far removed from our reality at all. Many corporations really do treat their workers like animals and are constantly looking for ways to eliminate care for them, because that will make them cheaper laborers.

"Although the film is not hopeful, it does encourage us to take an honest look at what we have allowed, and how we have continued to look the other way."

As the film unfolds, it becomes increasingly violent and upsetting. It forces viewers to ask themselves where they will draw the line, but it also helps us realize how complicit we all are in this system. Although the film is not hopeful, it does encourage us to take an honest look at what we have allowed, and how we have continued to look the other way—sometimes by choice, and sometimes because of the way that our economy is structured (which separates us from our impact on other people and the planet).

Contrary to its title, the film is not at all “sorry” to bother us—rather, it wants to bother us and to be a catalyst for efforts that might lead to a more equitable and livable economy.

Alexis Arambul is a graduate of Washington State University with a degree in political science and a minor in fine arts. Sarah Allison is a graduate of Fordham University where she majored in American Studies and minored in Spanish and Peace and Justice Studies.