Free Time: The Forgotten American Dream

by Lisa Mastny | June 20, 2013

New Dream spoke with labor historian Benjamin Hunnicutt, author of the book Free Time: The Forgotten American Dream. In the book, Hunnicutt describes how Americans have increasingly distanced themselves from their historical yearnings for leisure and free time, in favor of a culture of overwork—but that the dynamic may again be shifting.

Can you briefly summarize the gist of your book, Free Time?

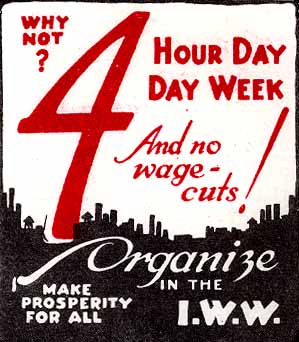

The book is about a mystery in U.S. labor history that I’ve been trying to unravel for 40 years. In the early 20th century, there was strong support for the “shorter hours” movement, and working hours were essentially cut in half as people began to embrace the possibilities of life beyond everyday work. In the 1920s and 1930s, people like economist John Maynard Keynes suggested that by the mid 20th century—and definitely by the 1980s—we’d be working more like 2.5 hours a day!

No one predicted that this process would stop. But after the Great Depression, working hours stabilized, and there has been no overall increase in leisure since. Even in the 1960s and 70s, there were predictions that the process would begin again—that there would be a return of short hours and increased leisure. But instead, there’s been a reversal. In 2005, Americans were working on average five weeks longer than in the 1970s.

So what happened? Why did something that looked so inevitable stop? Why are we now working 10 hours a day rather than 10 hours a week? In the book, I explore various ways to explain this phenomenon, looking at the role of things like consumerism, government policies to stimulate the economy, and machines and technology in contributing to longer hours and reduced leisure.

You talk a lot about changing views of “progress.” What was considered progress historically, and how has that perspective changed more recently?

Before the 1960s, people talked about progress in terms of higher wages and shorter working hours. Americans would have more of the good things in life, and more time to enjoy them. But we saw the ending of that dream, eclipsed by a new dream of full-time work and full employment for all. More recently, we are again seeing a glimpse of the old dream, with efforts to restart a shorter-hour process, but it is certainly not the dominant paradigm.

I n the book, I go through U.S. history to show how perspectives on progress have changed. It’s just the beginning of an effort to catalog what people were predicting would be possible if Americans worked less and had more free time and leisure.

n the book, I go through U.S. history to show how perspectives on progress have changed. It’s just the beginning of an effort to catalog what people were predicting would be possible if Americans worked less and had more free time and leisure.

Can you provide some specific examples?

In colonial days, religious folks like Jonathan Edwards and Samuel Hopkins were among the first to have this new vision of progress—they saw science and technology as bringing human reason to control nature, to free ourselves from her bonds, and to invest machines to do our work for us. Edwards, as part of the Great Awakening, talked about machines bringing people a “new freedom” to live a more humane existence, to realize our true humanity. There would be an appreciation of nature, a realization of the joy of community and of religious celebration.

Similarly, Hopkins wrote about how working less would create the potential for “disinterested benevolence”—in other words, in their new freedom, people would have more time to take joy in the joy of others.

In the early 19th century, organized labor took some of these ideas to create its own vision of progress. The American Labor Movement, in the 1820s and 30s, began to connect the dots and initiated a movement for shorter hours. The average work day at that time was dawn to dusk. So historically, the first demand from organized labor was the desire for leisure, for more time with family and friends—which is very different from their focus today.

Was it mainly men who were talking about shorter hours and free time, or were women also involved in the movement?

Women, such as those who worked in the woolen mills in Lowell, Massachusetts, were among the best spokespeople for this vision. They articulated a dream of becoming educated, of having more leisure, as a way to supplement the disruptions caused by industrialization—such as broken-up families.

They posited shorter hours as being the “unselfish” system that would allow time for community, sharing, and talking with each other, as opposed to the “selfish” system of capitalism. In their view, more time equaled a moral and humane existence. People would be able to get along better, and to build successful human relationships.

One writer at the time, Hulda Stone, offered a vision of a future that was not so much characterized by “technology as progress,” but rather was more humane—of successful families, engaging communities, the sharing of lives together. With free time, people would learn how to live together better. They would have time to read and communicate—to use their words to build community and relationships.

Even through the 20th century, many of the voices for shorter hours were women. They presented a critique of work itself, emphasizing the view that “working to live” was preferable to “living to work.” Work was not the entirety of life, and leisure could lead the way to higher progress.

Did these perspectives ever reach the mainstream of society?

Many bourgeois intellectuals were inspired by the labor movement. It had supporters like Walt Whitman, who felt that shorter hours would lead to more life, less work, and more energy to be invested in human relationships. Robert Hutchins of the University of Chicago was also concerned with the new leisure, as were craftsmen, architects, etc. Many were preparing for a new leisure and freedom, and building the infrastructure to accommodate it. Even Frank Lloyd Wright designed with the premise of building spaces where people could really appreciate and enjoy the new freedom that was coming.

There was broad support for shorter working hours, as people were drawn to the vision of a nation that was not so busy, where they would have more time to live their lives beyond the economy, beyond politics, and could work toward “higher progress”—a place where we could be fully human in our freedom.

There was broad support for shorter working hours, as people were drawn to the vision of a nation that was not so busy, where they would have more time to live their lives beyond the economy, beyond politics, and could work toward “higher progress”—a place where we could be fully human in our freedom.

So what has changed—and why?

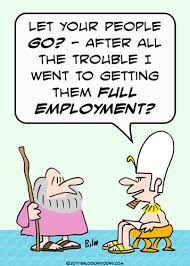

The biggest change is that today, progress is no longer seen as shorter hours and higher wages—the American Dream is now “full-time work and full employment for all.” Having free time is not viewed as a positive, but rather as a negative: free time equates to unemployment. It is now a leading economic indicator, with shorter working hours being an indication of lack of work, not presence of leisure.

What caused this fundamental shift? For one, President Franklin Roosevelt opposed the legislation to reduce working hours to 30 hours a week. Full employment was defined for the first time as being 40 hours (or better) of work per week. The federal government took on the role of being responsible for finding enough new work for people to do, to take the place of unemployment.

Another factor was the 1920s business community. They opposed shorter hours, because they saw the eight-hour day as being more productive, more beneficial to the bottom line. They didn’t want people paying attention to values and lives that were outside the economy. Henry Ford and others spoke of the need to promote the new economic gospel of consumption, and to encourage people to “not take this fantastic leisure.”

Proponents of productivity began to propagandize work as the center of life, building on Max Weber’s influential book The Protestant Ethic and The Spirit of Capitalism. Work was seen increasingly as an end in itself. In this new ideology, people’s full humanity could be realized in their jobs, and not through free time and leisure. This was really a 20th century development. It stemmed from the threat of leisure—it was a response to keep business going, to keep people at work. And it became the dominant imperative. Leisure became trivialized.

In one of your earlier books, Kellogg’s Six-Hour Day, you describe how the iconic cereal company bucked this trend and held on to a six-hour work day until as recently as 1985. Why did they finally transition to the more standard eight-hour day?

In a nutshell, belief systems changed, and values changed. Work became glorified, and many male workers and managers began to trivialize and feminize leisure and shorter hours.

Female workers tended to prefer the shorter hours—women had been outside the workplace for so long, and they were used to having the communication networks and free associations outside of work and men. But for men, increased leisure meant that they would be at home more, sharing the home more, and many men didn’t like this; they felt uncomfortable giving up status and control. They knew their role at work, but they didn’t have a clear sense of their place at home, so many welcomed the switch to longer hours that would also increase productivity and bring higher incomes.

In the 1950s, there was also rising concern about the “problem of leisure”—the idea that people would have too much time on their hands, which would cause stresses in the economy and in relationships. Even anthropologist Margaret Mead talked about the challenges that would arise from men being at home too much! The problem of leisure sparked the need to create more parks and recreational opportunities, to develop the infrastructure and community centers to accommodate increased free time. Without the infrastructure, it was believed that people would get into trouble.

But today we have the opposite problem, one of “overwork” rather than too much leisure. Can you explain?

Today, the issue has gone to the other extreme. The problem now is that people work too much, as opposed to having too much free time. Many of us don’t have the time to use all of that wonderful infrastructure that was developed in anticipation of the coming leisure, and as a result much of it has gone into disrepair or is underprioritized and underfunded.

In addition to overwork, we are also faced with the problem of unsustainable economic growth. In the book, I conclude that full-time, full employment is not sustainable. It depends on continued economic growth, and the reality is that economies can’t grow fast enough to keep up with full employment. It’s also not sustainable for the environment, culture, relationships, and equality.

In addition to overwork, we are also faced with the problem of unsustainable economic growth. In the book, I conclude that full-time, full employment is not sustainable. It depends on continued economic growth, and the reality is that economies can’t grow fast enough to keep up with full employment. It’s also not sustainable for the environment, culture, relationships, and equality.

Unfortunately, the reality is that advances in technology are going to bring “free time” to many Americans, whether we like it or not. We are already seeing this, in the form of rising unemployment. So our choice is whether we want to view this free time as “unemployment” or as “leisure.” If we don’t address the challenge of increasing leisure, we will have to deal with the effects of chronic unemployment and unrest.

Is there a solution?

A reasonable solution would be to replace chronic unemployment with shorter working hours for those who have jobs. Rather than the government imposing this, I think it will more likely need to originate in the free market. In other words, it may become increasingly acceptable for people to willingly choose to “buy their leisure” by cutting back their hours or not working (if they can afford to do so). Another option is work sharing, which leaves room to employ more people.

For many Americans today, the prospect of greater free time should be attractive, as it was historically. To modern-day proponents of leisure, economic “progress” means having the freedom to live out our lives. The Club of Rome’s conclusion is that economic progress is shorter hours and higher progress. In other words, people seeking higher progress will turn to forms of leisure that are time intensive (although not expensive) and less consumptive (requiring less disposable income). This would be more sustainable and allow for more freedom.

What did you hope to achieve in writing the book?

What I try to do in the book is to show people the old dream, of the good life, so people will make the choice to be “free” and to embrace leisure as a positive rather than a negative. It has to be free choice, not government imposed. But the government has an important role to play in building up the infrastructure—the parks, community centers, etc.—to accommodate people’s regained free time.

The bottom line is that our expectations about work are not paying off. They are not enabling us to realize our full humanity. For too many of us, work is drudgery, and it falls well short of what we are led to believe as the be-all and end-all. In light of this, we need to embrace other options for work and life.

Are you optimistic about a societal transition to increased free time?

Belief systems and values regarding work and leisure have changed dramatically in the last 50 years. The question is, can they change back? I see the future going either way. From the pessimistic viewpoint, the religion of work is so strong today, and we are so invested in it, that our concept of humanity has shifted.

Yet there are cracks in the surface. These cracks represent the old dream that is more healthy, that provides us with a way out of the environmental crisis. The idea that life can become more rich and less dependent on technology to express our humanity and progress. The idea that we can have viable community institutions that support our efforts to achieve higher progress. We need to recall that noble vision of what our nation can be.

I conclude the book with a discussion about efforts like New Dream’s, and the ideas of people like John de Graaf and Juliet Schor. The idea that we need to “find time.” Rising concerns about overwork versus leisure. The movement to restore old values of community and time. The politics of shorter hours. Even Hillary Clinton had ideas about increased family time, calling for a “family-friendly workplace” that would allow parents time to take off.

We also see encouraging signs in talk about the “experience economy”—the buying and selling of experiences, rather than products. I’m considering this as the focus of my next book, on the economy of experience and “saving work.”

Benjamin Kline Hunnicutt is an historian and professor at the University of Iowa. He is also the author of Kellogg's Six-Hour Day and Work Without End: Abandoning Shorter Hours for the Right to Work.