Governments Promote Planned Obsolescence, Too

by Addison Del Mastro | September 17, 2012

When we think of planned obsolescence, we usually think of corporations using savvy marketing techniques to get us to buy the latest gizmo or gadget. But we often don’t consider the role that governments can play in implementing planned obsolescence as well.

At times, well-meaning government policies have the unfortunate effect of encouraging large numbers of people to replace their “outdated” stuff with new items, resulting in significant resource waste.

Three examples are the digital TV switchover and the “Cash for Clunkers” program in the United States, and France’s abandonment of the Minitel computer network.

Digital TV Switchover

The U.S. switchover to digital television in June 2009, designed to make broadcasting more efficient and to enhance the viewer experience, resulted in tens of millions of analog TVs becoming obsolete overnight. The Electronics TakeBack Coalition called it “the largest government-mandated planned obsolescence campaign in history.”

Despite high-level strategizing on how to prevent an estimated 70–80 million television sets from being rendered obsolete—mainly through the use of converter boxes that would allow analog sets to receive digital signals—many consumers found themselves unprepared for the switchover, unable to receive vouchers to buy a converter box, or simply unable to obtain the boxes easily.

The result, combined with falling prices for sleek flat-screen TVs, was that millions of perfectly functional, and in many cases fairly new, analog televisions were thrown out for no real technological reason. Manufacturers of television equipment, of course, supported the switchover, while America's landfills and the environment suffered from the electronic waste. Junked TVs that aren’t properly disposed of or recycled can contaminate soil and groundwater, affecting local ecosystems and even human health.

It’s worth noting that no such outcome occurred during television’s other major transition: from black and white to color TV in the 1950s. Two competing systems for color transmission were developed and tested in the late 1940s and early ’50s, one by television manufacturer RCA and the other by the Federal Communications Commission. The RCA system, which more or less became modern color television, was designed to be compatible with the then-ubiquitous black and white sets; the FCC system was not.

Cash for Clunkers

Also in 2009, the U.S. government launched “Cash for Clunkers,” the informal name for the Car Allowance Rebate System, or CARS. The rationale for the $3 billion program, which allowed people to trade in their old car for a voucher toward a new one, was twofold: an environmental goal of getting older, gas-guzzling vehicles off the road, and an economic goal of stimulating the ailing U.S. auto industry by promoting new sales.

Despite these laudable ends, however, the execution of the program veered into the territory of planned obsolescence, ultimately resulting in large volumes of waste and costing both the government and consumers.

The use of the term “clunkers” by both government officials and private commentators didn’t help. Decades ago, there was something almost respectable about driving and caring for an old vehicle; Walmart founder Sam Walton famously drove an old Ford pickup. Many Americans own older or used cars, often because they are the only cars they can afford. When the government deems these cars “clunkers,” this creates a negative image of older cars—much as advertisers might cast “outdated” products in a bad light.

But it was the scrapping program that was the real display of planned obsolescence. Every single car taken in under the program was turned into scrap steel, whether a functioning Corvette or a rusted, limping conversion van. Many scrapped cars were worth more than the $3,500–$4,500 rebate, and collectible and rare cars were given no amnesty either. Furthermore, the engines—potentially the most valuable parts from old cars—had to be destroyed by replacing their motor oil with a solution known as liquid glass. The scrap steel was largely sold to China.

According to the research group Resources for the Future (RFF), the actual benefits of the Cash for Clunkers program were meager. On a positive note, the program did reduce overall U.S. carbon dioxide emissions by an estimated 9 million to 28.4 million tons, although at the exorbitant cost of between $91 and $288 per ton. RFF estimates that about 45 percent of cash-for-clunker vouchers went to consumers who would have bought new cars anyway, and the program boosted U.S. vehicle sales by just 360,000 during July and August of 2009, providing no measurable stimulus thereafter. Meanwhile, the program increased average fuel economy in the United States by just 0.65 miles per gallon.

And this doesn’t take into account the pollution caused by the production of the new vehicles that would not otherwise have been purchased. Even scrapping the cars required energy that would not have been used had the cars remained on the road. And by destroying the engines of older cars, the government may have reduced the supply of parts for remaining old cars, making it necessary for owners to either pay more for parts or buy a new car that they otherwise wouldn’t have needed.

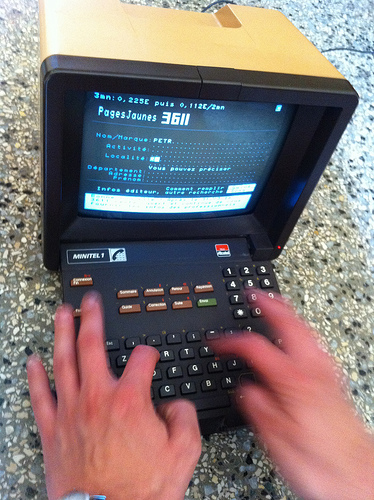

Minitel System in France

The U.S. government isn’t the only one to encourage planned obsolescence through its policy choices. Decades ago, entrepreneurs in France developed the Minitel, a kind of pre-Internet, telephone-based networking system that was managed jointly by the French government and the company France Telecom. Although the system was profitable to the tune of $43 million as recently as 2010, the government insisted on scrapping Minitel just this June because it was “obsolete.” The service still had 1 million users.

There had been plans to close the Minitel system earlier, in 2008, but there was a huge consumer backlash. The date was then moved to late 2011, but still users protested. And so it was that France finally ended a profitable, useful service in 2012. This, of course, is excellent for computer manufacturers and Internet providers, but not so good for the French consumer.

There had been plans to close the Minitel system earlier, in 2008, but there was a huge consumer backlash. The date was then moved to late 2011, but still users protested. And so it was that France finally ended a profitable, useful service in 2012. This, of course, is excellent for computer manufacturers and Internet providers, but not so good for the French consumer.

The striking thing about the Minitel phaseout is that the system was still profitable. Businesses generally use planned obsolescence as a way of increasing profit—but France used it to eliminate a system that was still pulling its own weight.

Contrast this with Sony’s Playstation 2, a video game console that had one of the longest lifespans and production runs of any game console ever, at about 10 years. Due to its popularity and profitability, Sony continued to produce it long after it had been replaced by a more advanced generation of game consoles. Although private companies are not always this obliging to their customers, the promise of continued profits can at times discourage a manufacturer from pushing early obsolescence.

Unlike private companies, governments are not beholden to profits and can use the force of law to mandate initiatives that amount to planned obsolescence. Despite the noble goals of many government programs, without precautionary measures to reduce resource waste, the result can be one that has unfortunate consequences for both people and the planet.

Addison Del Mastro is a student at Drew University and an intern with New Dream.