iFixit.com: Boldly Empowering Us to Repair Stuff Ourselves

by Lisa Mastny | November 14, 2012

It wasn’t long ago that we could take a broken-down stereo or malfunctioning toaster to a neighborhood repair shop to get it fixed or overhauled. But these days, it’s nearly impossible to find these types of services. For most of us, it ends up being easier—and cheaper—to just buy a new one, even if we don’t necessarily want to relegate the old one to the trash heap.

But thanks to the Internet, we now have other options. The recent resurgence in the repair movement is being boosted in no small part by websites like iFixit.com, which seek to empower people when it comes to “do-it-yourself.” Through its clean, user-friendly interface, iFixit offers free manuals and advice for repairing thousands of different products, from the latest iPhone or Dell laptop to vacuum cleaners, lamps, cameras, and more.

“Once manufacturers began using more complex technologies—especially electronics and computer chips—it became harder for people to get the information they needed to repair or service products, and the local repair tech industry faded away,” explains Kyle Wiens, co-founder and CEO of iFixit (pictured above right). “But today, the Internet is tipping the balance around the world.”

iFixit’s philosophy is simple: publish it, and they will come. The site’s step-by-step service manuals respond to a broad range of common repair needs, from battery replacement to power source problems, detailing the tools and replacement parts required to do the job and providing clear photos and instructions. All of the information is free and open source, meaning that community members from around the world can contribute their own knowledge and tips, as well as provide feedback.

In October 2012 alone, iFixit helped an estimated 5 million people repair their broken stuff. To put this in perspective, however, during that same period, Apple sold more than 5 million iPods alone, indicating the magnitude of the repair vs. consumerism challenge.

Among the site’s most popular searches are for iPhones (fixing dropped or damaged phones), Xbox game consoles, and home appliances like the Starbucks Barista espresso machine. The site focuses primarily on hardware repairs—helping people address damage or malfunction that’s not covered under warranty—rather than on software issues, since it’s often relatively easier to obtain software support from the manufacturer.

“The real gap has been with the physical product,” explains Wiens. “Collectively, as a society, we have forgotten what’s inside things—what makes them tick. We’ve shipped all of our manufacturing off to Asia, so very few Americans have a clue about what’s going on inside that plastic or metal casing.”

Filling a niche

Wiens and co-founder Luke Soules started iFixit in 2003 in their dorm room at Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo, after they were trying to repair an Apple iBook laptop and couldn’t find a service manual. Having worked at a certified Apple repair shop, Wiens knew that the manual existed but was unable to find it online. “Like many manufacturers, Apple essentially uses copyright law to prevent distribution of its manuals—in part to enforce planned obsolescence,” he explains. “They don’t want this information in the hands of independent service shops.”

"Like many manufacturers, Apple essentially uses copyright law to prevent distribution of its manuals—in part to enforce planned obsolescence.”

So Wiens and Soules began writing their own manuals, starting with common repairs for six different Apple laptops, and posted the information online for free. They got 10,000 hits the first weekend. As iFixit grew, the pair initially funded the site by disassembling broken computers and selling the components.

Today, iFixit offers thousands of different service manuals, including 250 guides for cell phones alone. Yet this still covers only 50 percent of the phones currently being marketed, showing how big the challenge is to provide practical information on repairing all of the consumer products that we enjoy. And the site doesn’t come close to publishing manuals for the thousands more still-usable but older phone models that have been deemed “obsolete.”

Knowing that not everyone is a tinkerer or has the tools to deal with tiny electronics components, iFixit seeks to make repair work as easy and accessible as possible. In addition to providing extensive repair advice, the company also designs and sells its own tools—including a screwdriver kit with 54 bits that can be used to take apart “almost every consumer product you could buy.”

Tool sales, along with sales of parts and upgrades, help iFixit cover the cost of offering all of their repair knowledge for free. “We had—and still have—the ideology of a non-profit. We just found a way to make it financially sustainable,” says Wiens.

And the model is clearly working. For several years running, iFixit.com has been featured on the Inc. 5,000 list of the fastest growing companies, ranking #90 in the retail industry sector. During the last three years, the company has grown 146 percent—earning $5.9 million in revenue in 2011—and added 21 employees, bringing the total to 35.

Meanwhile, the website receives glowing feedback from users, many of whom share their own repair stories and even post pictures of the process, thus strengthening the usefulness of the site to the iFixit community. “People are learning from one another, not just from us,” Wiens explains. “It just happened—it’s nothing we set up at an organized level. They play a big role in determining what manuals we feature. The community decides what direction iFixit goes.”

Building a global community of fixers

iFixit doesn’t do much advertising, so most people find the website through an Internet search or by word of mouth. Most one-time visits are from service technicians—people who make a living doing repair work on a specific brand or item, like computers or washing machines.

“We’ve found that iFixit is a great training ground for technicians,” says Wiens. “They download the manual they need, then they use it to repair the same item over and over again.” But most of the site’s repeat visitors are everyday consumers, who browse the site on an as-needed basis every time another product breaks.

While roughly 50–60 percent of site visitors are based in the United States, an estimated 35 percent are in Europe and a small but growing share is in the developing world. Says Wiens: “We’ve been blown away by the stories. One guy wrote us from the jungle in Cameroon, looking for advice on fixing a satellite dish and generator.”

Another story comes from El Salvador, where an iFixit employee came across a man running a cell phone repair kiosk. When asked about where he learned how to repair the phones, the man finally admitted that his “secret tool” was iFixit.com.

Moving forward, iFixit hopes to continues to expand its product coverage, though Wiens admits it will be difficult to keep up with the many thousands of new products that come on the market each year. “Repair is not a niche market—it applies to everything. We want to help with any and all products, and to expand into new areas.”

He also wants to work more directly with manufacturers, rather than emphasizing the negative aspects of their production. “If you frame it the right way, you can design an approach where repair makes them money.”

The role of consumers

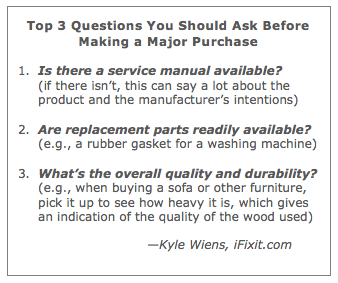

Another key goal for iFixit is consumer education. “We need to better educate consumers about what constitutes a reliable, repairable product and what doesn’t,” says Wiens. “When people go to Home Depot, they have no idea which tools are more repairable than others. There’s a serious lack of knowledge about how long something will last. We can find out whether a washing machine is energy efficient—but will it break in four years? There’s not much out there pointing consumers toward this information.”

iFixit is trying to fill the void by offering its own limited rating service, known as “Gadget Teardowns,” which focus mainly on items like cameras, cell phones, and computers. Staff identify the most popular gizmos released in a given month, disassemble and photograph them, and then assign a “repairability” score for each. But given the expense of buying and evaluating the products, these efforts are limited to some 30–40 products annually.

iFixit is trying to fill the void by offering its own limited rating service, known as “Gadget Teardowns,” which focus mainly on items like cameras, cell phones, and computers. Staff identify the most popular gizmos released in a given month, disassemble and photograph them, and then assign a “repairability” score for each. But given the expense of buying and evaluating the products, these efforts are limited to some 30–40 products annually.

Wiens notes that for electronics in particular, repairability trends are quite negative. “Most products are non-upgradable. Manufacturers may want to compete on quality, but there’s a race to the bottom. People have come to expect cheap goods—but it comes at the expense of quality.” He points to some exceptions, like outdoor clothing retailer Patagonia, which promotes the repair and recycling of its products and is able to justify its premium price. And Wiens says that Dell makes computers that are “more repairable and upgradable than the competition,” although “anything powered by a litihum-ion battery is basically designed to fail after 12 to 24 months.”

But it’s not just the manufacturers who are at fault: consumers are culpable, too. In market experiments, Apple found that laptop buyers opted to purchase the MacBook Air over the similarly priced MacBook, even though the MacBook Air had a slower processor, was harder to upgrade, and was essentially “designed to fail.” “It was simply because the Macbook Air was thinner and sleeker that it outsold the MacBook,” Wiens explains. “Consumers went for the item that was as thin as possible over the item with better product life.”

"There needs to be a structural shift toward the understanding that repairable, long-lasting products are better.”

Wiens calls the iPod phenomenon another “watershed moment” for our culture, revealing how consumer psychology has fed the demand for throwaway devices. “Essentially, when the first wave of iPods all failed a decade or so ago now, we all collectively shrugged and then went out and bought new ones. How is it that Apple is selling people a new music player—a device that just plays music—every two years?! It’s because when the battery runs out, most consumers assume that it’s their fault that the iPod stops working, because it’s ‘old’ and needs to be replaced. But really, there’s no reason that an iPod shouldn’t last 10 or 20 years, if we’re able to replace the battery.”

With this in mind, one of iFixit’s most popular repair questions is about iPod battery replacement—a relatively easy fix that shouldn’t take more than a few minutes. Yet Wiens estimates that no more than .01 percent of iPod owners have replaced the device’s batteries, opting instead to buy a new player that essentially serves the exact same purpose.

One of Wiens’ big goals through iFixit is to change people’s perception about the value of older or used products. “We’re trying to boost the economic value of used products. We make it faster and easier to make a repair, so that it’s ultimately cheaper to do so, which boosts the value of the product.”

But the problem is also cultural, he explains. “People don’t make educated decisions about repairability. There needs to be a structural shift toward the understanding that repairable, long-lasting products are better.”

Lisa Mastny is Senior Editor and Director of Publications at New Dream.