Josef Beery: Connecting Community Through Art and Books

by Lisa Mastny | December 11, 2012

New Dream spoke with Josef Beery, an artist, printmaker, and community activist in Charlottesville, Virginia, about his passion for the printed word and his efforts to broaden the dialogue around sharing, simplicity, and community connection.

Can you briefly describe your work as an artist and printmaker?

I began my adult life, like many of my contemporaries, placing the "artist" on the pedestal. I knew that creative activity had always been very rewarding in my own life, but it was always a distraction, a recreational activity I never really felt "OK" to pursue. It took decades before I began to acknowledge that creativity is an essential port of each of our natures as human beings. An "artist" is simply someone who recognizes that their creative impulses to explore and discover are just as valuable as the more obvious drives we feel compelled to follow

In my own life, drawing, writing, and printmaking became the media in which I found expression. Drawing and writing because they are a form of focused meditation which leads to a deeper understanding of our world, external and internal. Printmaking because it is a way to easily share this drawing and writing with others.

Printmaking is a fabulous medium that introduces tools and materials into the process of making and depends on them to play a strong role in the creative process. Finally, this very ancient craft is accessible to anyone who can make a fingerprint or a footprint.

You started out working with drawing boards and pasted materials, and have since joined the “digital revolution.” Was this a difficult transition for you, philosophically and/or technically?

I feel very blessed to be alive during the digital information revolution. The pace of technological change has been jarring and often difficult for me to keep up with. It is this confusion that has resulted in my focusing my attention on more historical hand-centered tools and processes at the same time that I have been learning the new digital techniques.

You’re a big advocate of books and strongly believe that “the printed word endures.” But in the era of digital everything, how important is it for physical books to remain a part of our lives?

Books occupy a magical place in our lives. They are both tool and symbol. Think about the importance my generation has given to books: the book is the ultimate symbol of power and law in so many political and religious systems. But more importantly than that, we see in the book a physical expression of ourselves as living beings.

A book is an extension of the life of a human being—a physical encapsulation of the interaction of human beings with things and ideas. This is a fundamental concept that even preschoolers grasp when they feel motivated to make scrapbooks and story books.

Digital media have given us a multitude of new means for expression and communication, but while these add to ways for creating value in our lives they do not change the essential physical and material need we have to hold a book within our hands, turn the pages, and quietly lose ourselves within the ideas represent by printed words and images.

In your presentations and classes, you speak about the importance of “hand/heart coordination.” What do you mean by this?

I believe that most of the challenges we face in society today—failures in social systems, exploitation of natural and human resources—are based in the fact that we as individuals are encouraged to listen to very primal fears within our souls instead of the natural love and compassion residing in our hearts.

Many of us work at jobs that we do not enjoy or, most troubling of all, that involve activities that are counter to our own personal ideals. We do this because we feel compelled to, if we are to assure the survival and security of ourselves and our loved ones.

Finally, living surrounded by the constant media clatter about what we "need" and "must have" to be happy, makes it very difficult to truly listen to the urgings of our loving hearts. If we can find the peace and the time to listen to our hearts, and then put our hands to the work of our hearts, I believe many of the ills we struggle with in human society would disappear.

You’re a strong advocate of exploring ways of living that center less around consumption and competition, and more around one’s connection to place, others, and community. What are some examples of this?

I think it is clear that groups of individuals competing with one another will never do as well as groups of individuals working cooperatively. Professor Martin Nowak at Harvard recently published an article in Scientific American about the dynamics of cooperation in the evolutionary process. Unfortunately, free enterprise has mucked up our understanding of this concept, resulting in a society that builds its very existence on the social and political conflict between these ideas.

Advocates of the "more is more" philosophy are quick to point out that without the production of massive amounts of material goods and a concomitant frenzy of consumption, our economy would no longer have a life-giving engine. These commentators overlook the fact that we as humans have plenty to "do" without just producing and consuming widgets. We have the infrastructure and services of a growing problem-solving society to create and sustain.

In your own life, you decided to move from a very urban setting in downtown Charlottesville to a rural community in a largely Mennonite area. What have you learned from this experience?

In 1980, I finished college and lived in downtown Charlottesville in a diverse socio-economic community, one recovering from the racial stresses of the sixties and the economic downturn of the seventies. It was a time of social stagnation, but the flip side was a very nurturing place for artists to live and work. For the next 20 years I flourished in this environment, but by the turn of the millennium, our community had been "discovered." Real estate and business began to boom and I felt it was time to pursue a long-time dream of rural living.

Not seeking isolation, just an environment in a more natural setting, I sought out a community to move to. I was fortunate to find a small community of Mennonites who welcomed me as a neighbor when I moved into the oldest farmhouse in the area. Life in the country can be challenging—one lives a bit closer to the necessities of life—and it is in community that folks can provide support for one another as we share struggles and joys of life.

In recent years, you’ve taken your views about lifestyle and community “to the streets” through what you call “power-pole political protest posters.” Can you explain what these are, and what motivated you to take this step?

I have been very inspired by young people, their concern for creating a better society and the energy they bring to that challenge. I am still part of a very active arts cooperative in downtown Charlottesville in what is now a very busy city location.

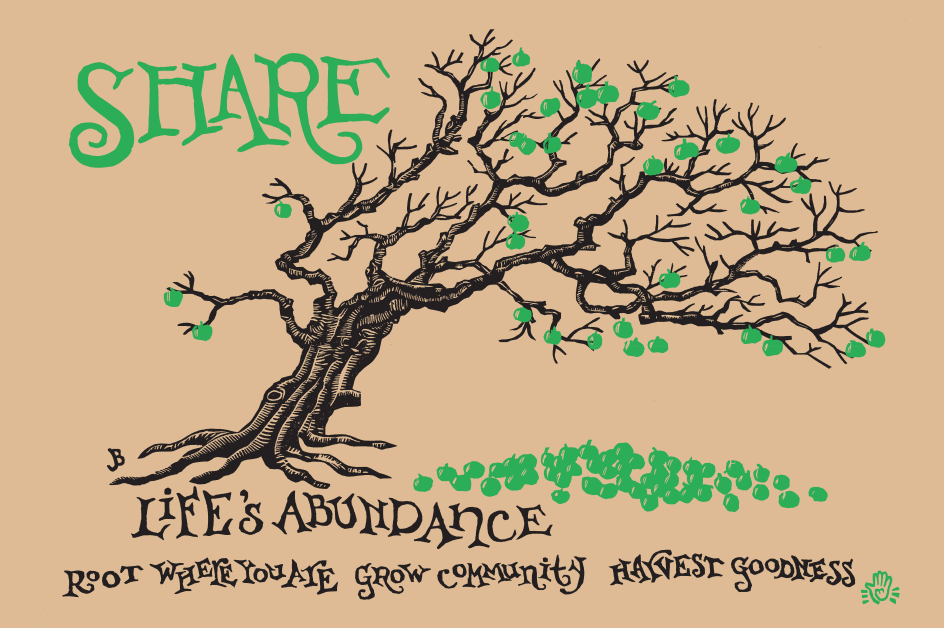

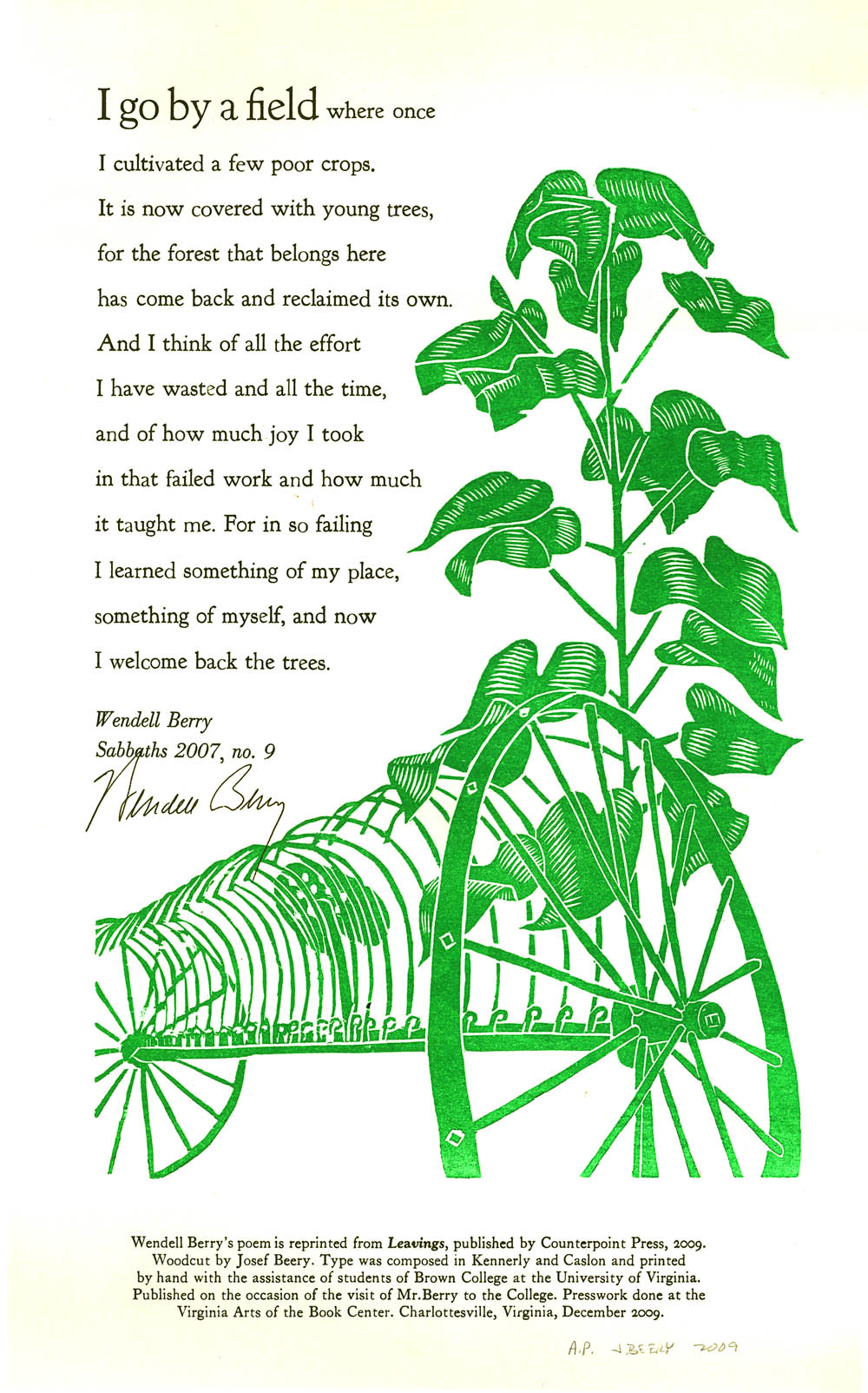

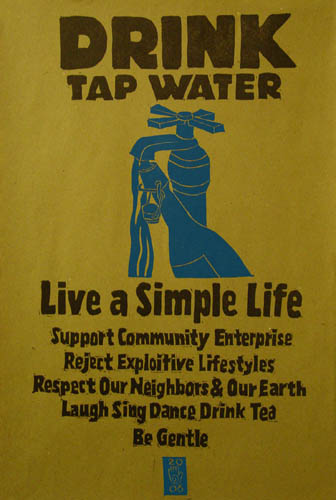

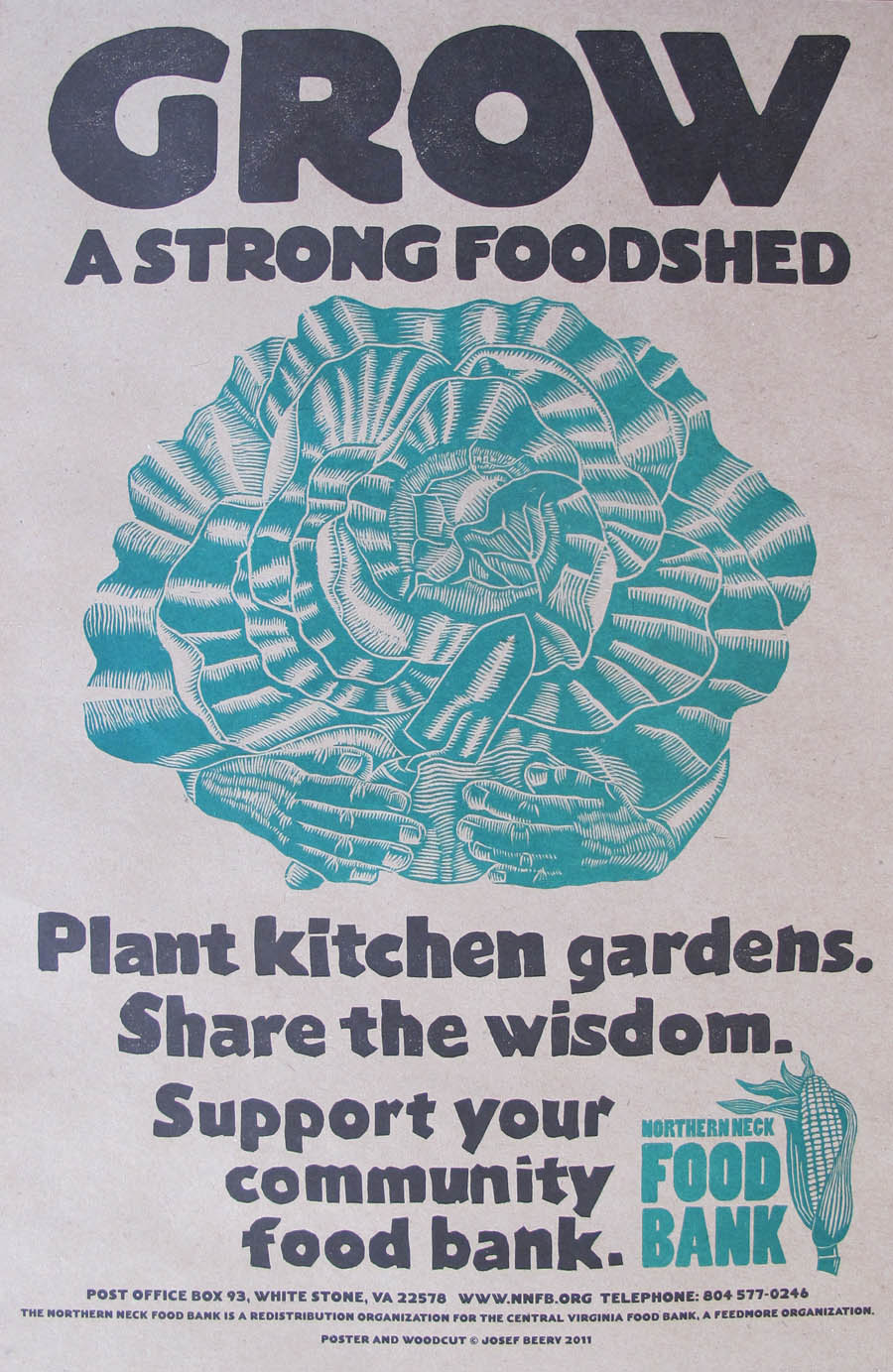

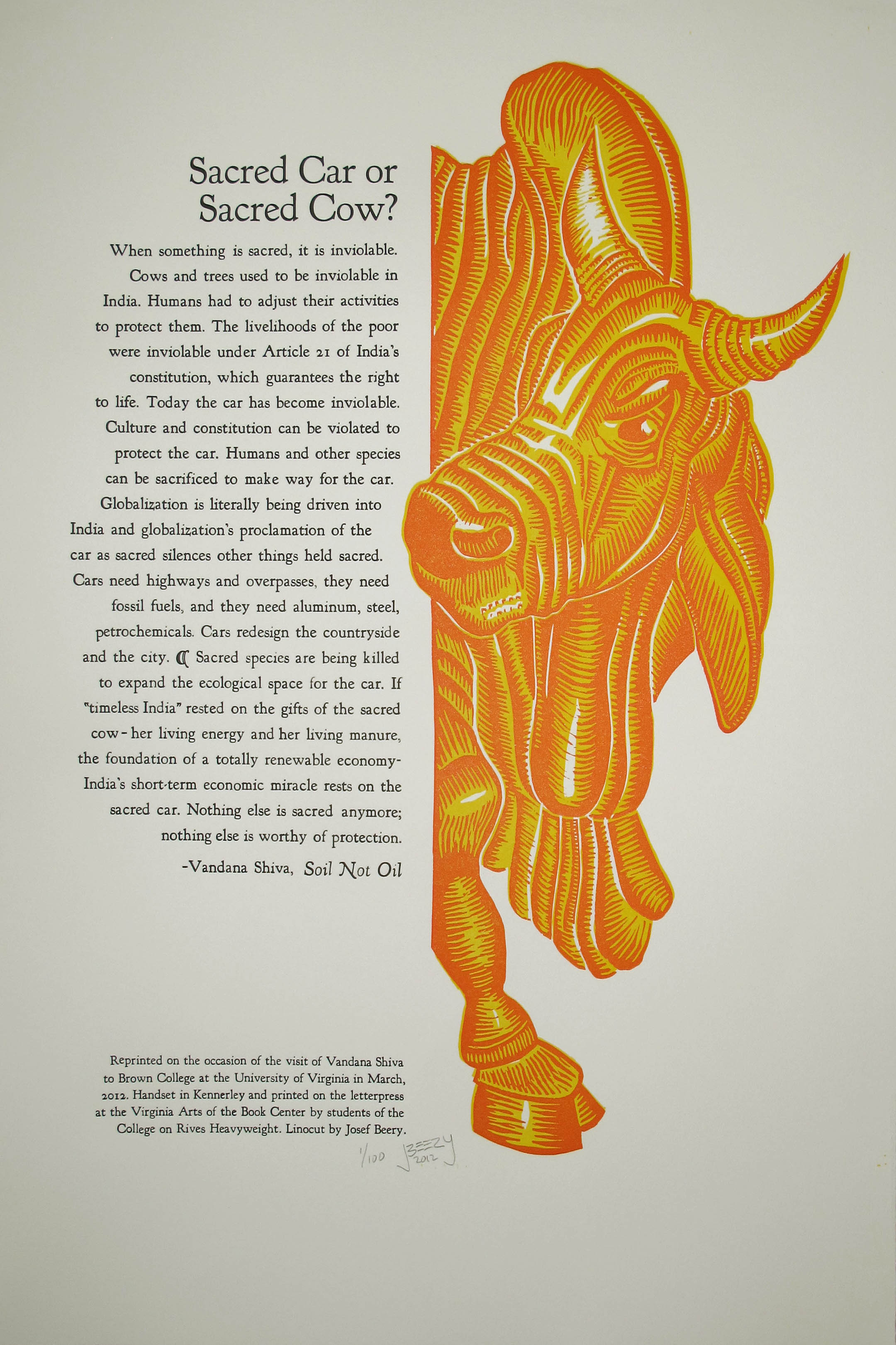

I discovered that by printing posters using linoleum or wood on my letterpress, I had an outlet for many of the strong political feelings that grew out of the struggles of the last decade. Posting them on power poles outside my studio window, I could watch their effect on passing traffic. I was flattered that this became a perfect way to "publish" my comments as the posters were "stolen" from their postings to be reposted in living rooms and kitchens.

You’re particularly concerned about the disappearance of shared public resources, like libraries and public schools. What is society losing with the erosion of the commons?

This is an amazing time for me, as the art form that interests me the most—printing and the book—becomes a huge focus of the digital information revolution. We are reinventing the book and reconsidering the services that we have associated with it for so long. Our American system of a democratic society was built upon the foundation of an educated electorate (Jefferson and Franklin). This requires strong public libraries and schools. But interestingly enough, the idea of a public library is contrary to our attempt to commodify intellectual property.

Almost 250 years after our nation's creation, we would never think to use public money to create institutions in every community to allow individuals to read materials that the free market expects them to pay for. It was a revolutionary and subversive idea—an idea that we will have to struggle to protect. I am encouraged that the public library spirit is alive and growing in some of the grassroots movements that have emerged on the Internet—projects such as the Little Free Libraries and BookCrossing.

Most people know about Charlottesville because of its connection with Thomas Jefferson, a passionate reader and overall renaissance man. You’ve done a lot to help Charlottesville flourish as a “book town.” What did this involve, and do you have suggestions for how other communities can take similar steps?

Charlottesville has been a fabulous place to be involved with the book. Being a university town, it is filled with readers and book stores. It has been the perfect location to build a book festival, the Virginia Festival of the Book, which attracts writers and readers from across the country in a long weekend of celebration. And then additionally, this interest in books has supported a growing book arts scene, centered around a cooperative book arts center, the Virginia Arts of the Book Center.

Other woodblock posters by Josef Beery:

Josef Beery is a graphic artist specializing in the design of books and publications for educational institutions, museums, historic sites, and literary publishers. He is also a book artist and printmaker creating handmade chapbooks and broadsides for poets and poetry presses. To learn more, visit his website at www.josefbeery.com.