Vance Packard: Unsung Leader of the Environmental Movement

by Addison Del Mastro | August 15, 2013

Have you heard of Vance Packard?

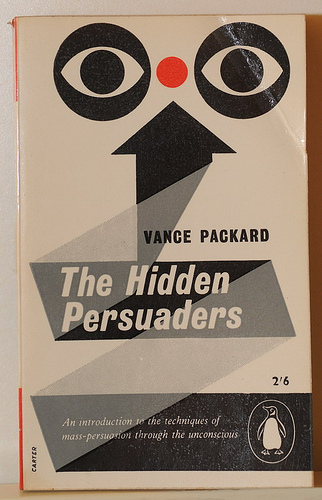

Maybe he was mentioned briefly in an article on American social criticism, or in a footnote about advertising and consumerism. Possibly, you’ve even heard that he wrote a book about “subliminal advertising.”

Unfortunately, most people haven’t heard more about him than a brief mention of his name. Vance Packard is an extremely important—and under-recognized—writer who laid foundations in his work for many aspects of the modern movement against consumerism.

Writing from 1957 to the early 1980s, Packard covered a host of topics from urban sprawl, resource depletion, and the limits of economic growth to planned obsolescence, the declining lifespans of consumer goods, and the rising amount of advertising in society.

Packard was not, in his own time, an environmental writer. He did not claim to be one, presenting himself instead as a journalist and social commentator. Looking back at his work today, however, it’s clear that his writing has been a major, and sometimes quite direct, influence on modern environmentalism.

Who Coined “Consumerism”?

In short, Packard did. That’s right: a person most of us have never heard of coined a term we use every day. The word had existed previously, but indicated the positive idea of consumer advocacy or working in the interest of consumers. Packard cleverly tweaked the emphasis of term, defining it on the dust jacket of his 1960 bestseller The Waste Makers: “the ever-increasing commercialism of every aspect of our lives.”

While the reference is brief, it is recognized by the Oxford English Dictionary as the first use of the term with its modern, anti-consumption meaning. Packard was certainly not the first to write against excessive consumption, but he was the first to coin the term by which it would be known for the next five decades.

The Story of Stuff, 1960

Packard’s The Waste Makers clearly laid foundations for another important and more widely known environmental book: Annie Leonard’s The Story of Stuff. In arguing for reduced consumption, Leonard makes the case that the real cost of consumption is far greater than its financial cost, it’s the hidden environmental and human costs.

Packard actually made this argument as well in 1960. He discussed the scrap steel industry, describing piles of rusting automobile hulks with little value, side-by-side with the alarming decline of high-grade iron ore. Packard blamed subsidies for virgin steel—as well as the prevalence of steel plants tooled for ore rather than scrap—for a price system that incentivized the depletion of a vital resource.

Leonard added a more coherent thought process to Packard’s fact-finding, but Packard pointed out the failure of price systems decades ago.

Paste Pots Were Only the Beginning

Packard’s journalistic method meant that his books were filled with incredibly prescient ideas and observations. In 1960, he wrote about the millions of dollars that product packaging alone cost consumers, including that an aerosol whipped cream can expired with a great deal of cream left in the bottom.

One book reviewer mocked Packard’s seemingly mundane observations, “Packard’s targets are often not worthy of his attack. Steffens exposed the shame of the cities; Ida Tarbell did battle with the Standard Oil trust; Packard complains that the brushes in paste pots fail to reach the bottom.”

At the time, perhaps only Packard cared about paste pots. Today, though, everyone knows what Packard was seeing when a two year old laptop kicks the bucket or a $200 appliance control board dies a week after the warranty. Packard saw that the ethic of thrift was being rapidly eroded, and the paste pot that could not be emptied was a striking, if mundane, example of the new ethic of waste.

Reading Packard Today

Obviously, Packard’s books today have a certain dated nature to them. There is only a hint of the systems thinking that dominates environmental thought now, and there is a less urgent environmental crisis. His writing, however, endures not because he was an academic or theoretician, but a journalist who read trade magazines, reported the signs in shop windows, and spoke to everyday people.

Packard's three most important works, The Hidden Persuaders, The Waste Makers, and A Nation of Strangers, contributed more to the modern environmental and anti-consumerism movement than most people know, and he deserves greater recognition for his place in history.